Research

Behavioral evolution – from natural genetic variation to behavioral divergence

Despite the fact that behavioral traits are often highly heritable, can vary tremendously between populations and species, and are often essential for survival and reproduction, the mechanisms underlying behavioral evolution are only beginning to emerge. The dearth of examples connecting genes and behavior may be due to several hurdles; many behaviors are difficult to quantify robustly, are presumed to have a polygenic basis, and likely are affected by complex neural processes. However, a lot of progress has been made recently. First, machine vision approaches make it now possible to often perform (semi-)automated, objective, high-throughput behavioral phenotyping. Second, genes-to-behavior links can and have been shown to be straightforward for genetic changes that act through the processing of sensory information. Third, our understanding of neural cell types and circuits is advancing at a rapid pace. Nonetheless, additional studies on variation in behavior in the wild are needed for generalities to emerge. Systems with natural replicates of closely related populations and species – in which comparative analyses are not complicated by issues of high background divergence and orthology/paralogy – are likely to prove particularly powerful. North American deer mice of the genus Peromyscus are such a system, comprising more than 50 species and many more subspecies that have (often repeatedly) evolved striking differences in ecologically-relevant behaviors. My current research is focused to a large extent in uncovering how coding or regulatory genetic changes act through the nervous system to result in behavioral differences in these mice.

Population genomics – leveraging the information stored in genomes

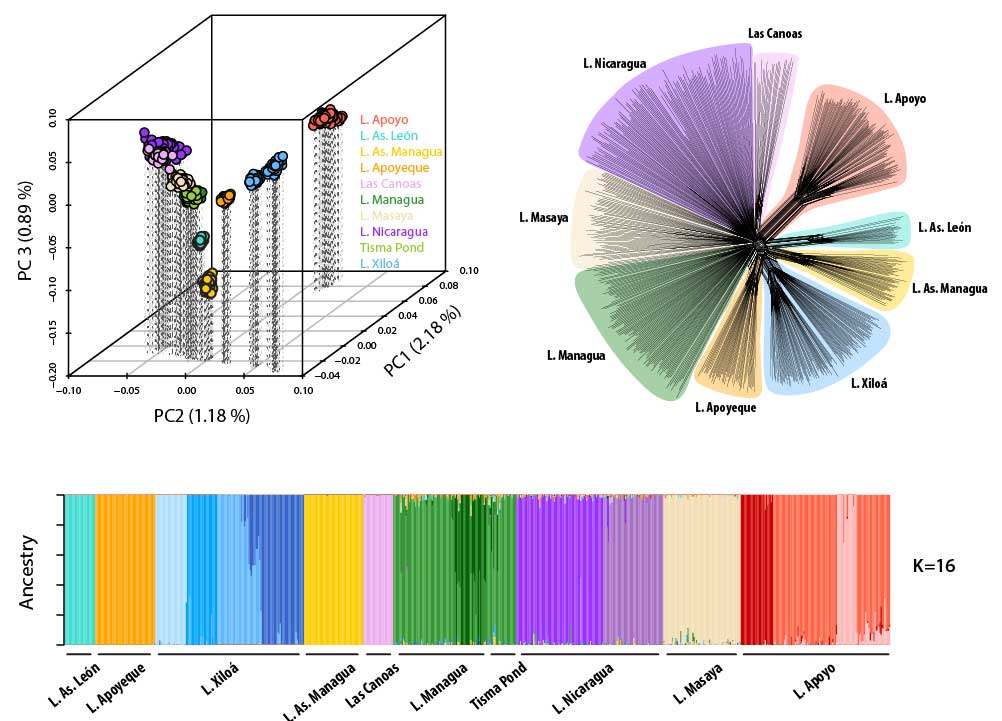

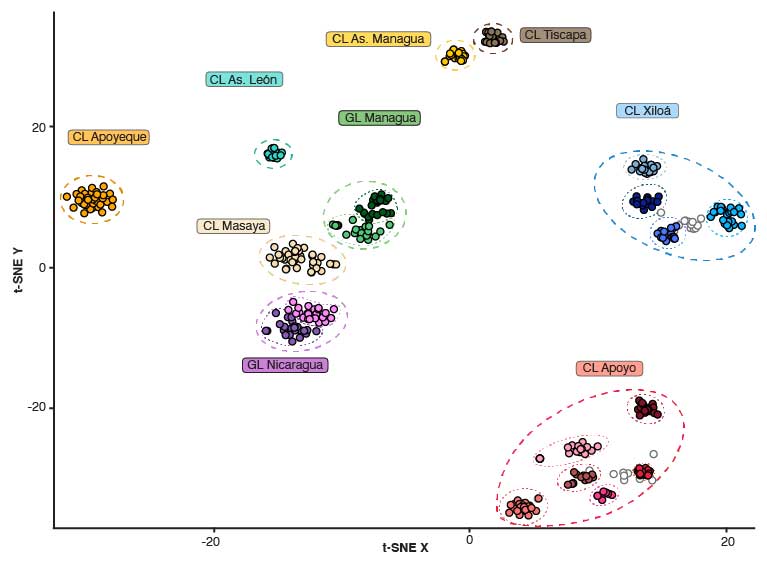

Based on a solid foundation of theoretical population genetics, the information stored in molecular markers can provide a window into past and contemporary evolutionary processes. While acquiring this sort of information at the population level used to be a rather laborious wet lab task, high-throughput sequencing methods have dramatically changed the pace of data generation and thereby revolutionized the field. I have personally experienced this rapid progression, having worked with mtDNA markers, microsatellites (Elmer et al. 2010), and AFLPs (Kautt et al. 2012) in my undergraduate studies, with RADseq data during my PhD (Kautt et al. 2016, Franchini et al. 2017, 2018), and finally whole genome sequences in the last couple of years (Kautt et al. 2020). Once the data is obtained, it can be used in a number of (often complementary) ways. Some of the most common applications for which I routinely use population genomic data include:

- Demographic inference: information obtained from (presumably) neutral markers can be used to infer the demographic history of one or several populations. Knowledge about divergence times, the presence and extent of gene flow or admixture events, and population size changes can be highly informative for interpreting and understanding the processes driving speciation. Even more directly, different competing hypotheses (e.g. primary divergence-with-gene-flow versus secondary contact) can be explicitly formulated in demographic models and their relative likelihoods can be evaluated within a rigorous statistical framework.

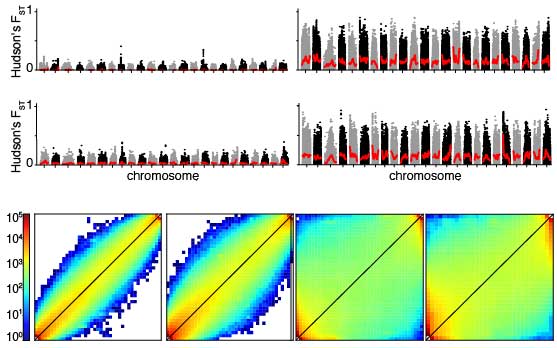

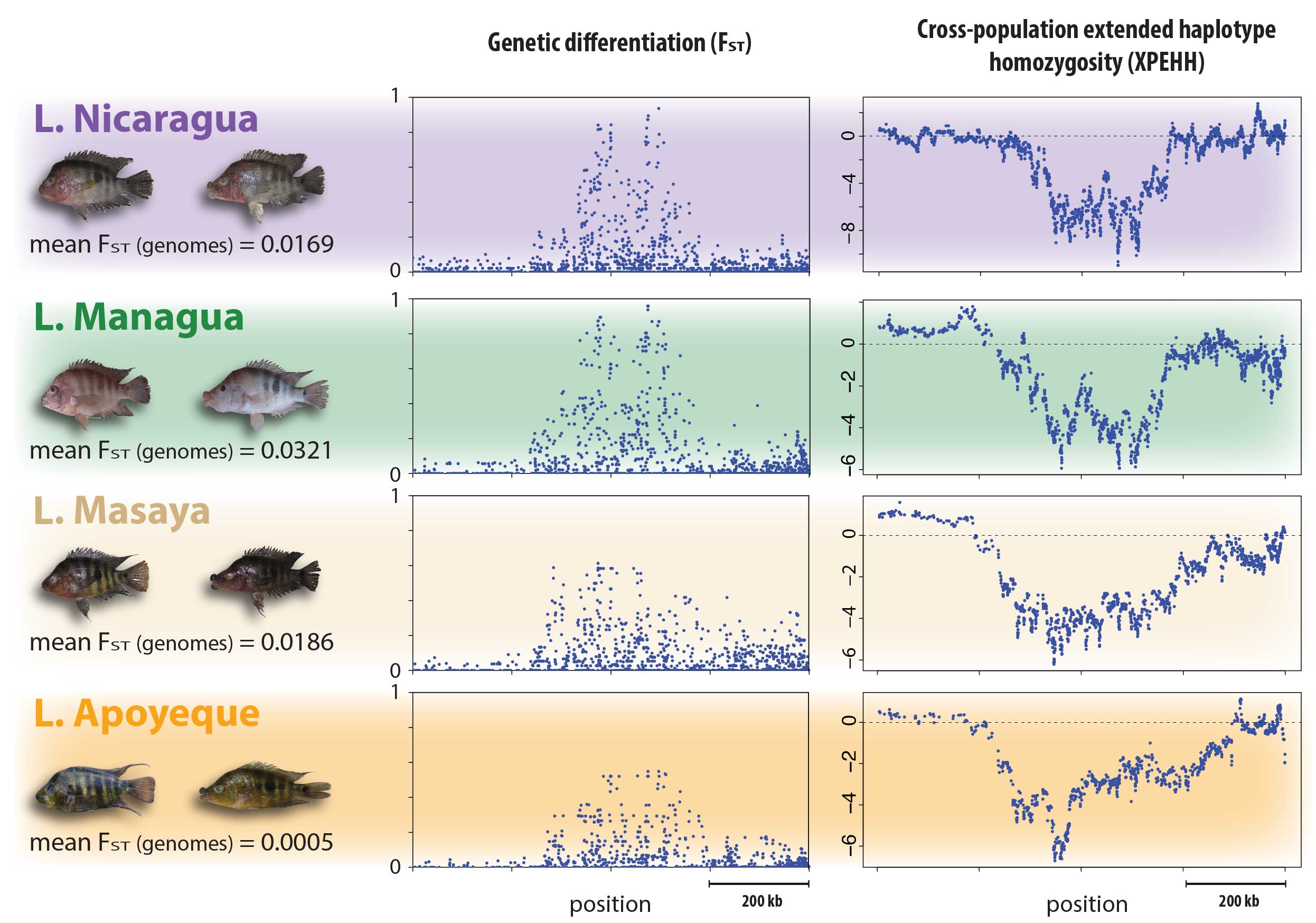

- Genome scans: often explicitly considering their inferred demographic history, the genomes of populations and adaptively diverged species can be screened for signatures of selection. Genome scans can thereby provide insights into the dynamics of divergent selection and gene flow and the overall build-up of genome-wide differentiation over time (i.e. the genomic landscape of speciation). Especially in the early stages of divergence, this approach can also proof powerful to elucidate candidate genetic loci underlying adaptive traits. Potentially, this approach can also reveal traits that were not even known to be under selection or diverging before.

- Genome-wide association studies: depending on the experimental design and the availability of phenotypic information for certain traits of interest, molecular markers spread across the entire genomes are also an incredibly powerful source of information to infer the genetic architecture of traits and potentially pinpoint their genetic bases. I want to make sure to mention here that this list is by no means exhaustive. Also, the real power of empirical population genomic data is often only unlocked in combination with extensive knowledge about the natural history and biology of the organism of interest, experimental manipulations, and/or genomic simulations.

Parallel phenotypic evolution – is evolution predictable?

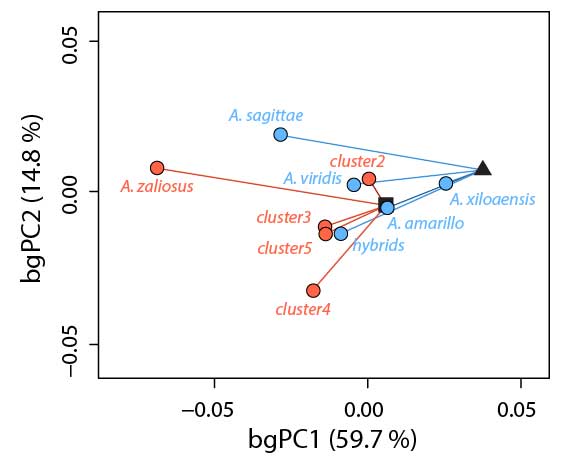

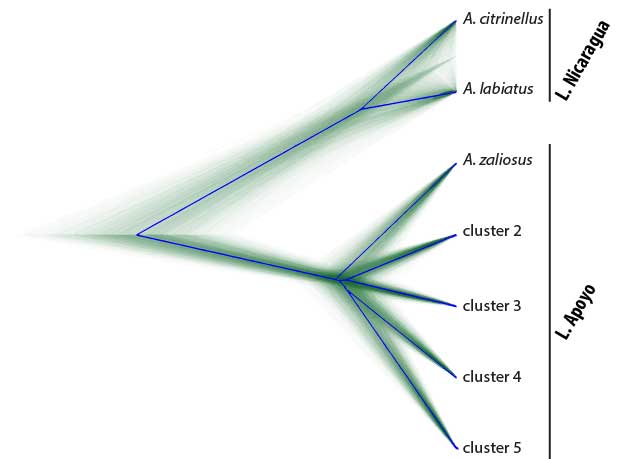

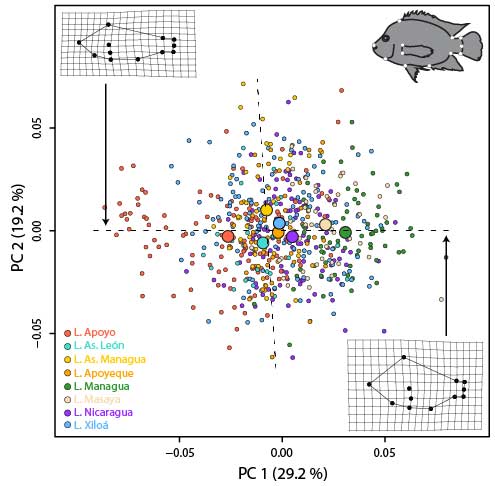

The repeated evolution of similar traits, a process called parallel or convergent evolution, has fascinated evolutionary biologists for a long time. And for good reasons. First, parallel phenotypic evolution showcases the power of random mutations together with natural selection to arrive at the same or a similar phenotypic “solution” when exposed to a shared ecological challenge. Second, whenever we witness a case of parallel phenotypic evolution, we may ask whether the same or different genetic and molecular mechanisms contribute to it. In other words, are there redundancies or multiple “solutions” to a certain phenotypic optimum at the molecular level. On the flip side, when we don’t see parallel phenotypic evolution although we’d expect it based on certain ecological conditions is it because of the stochastic nature of mutations and/or evolution in small populations or is it maybe because we have overlooked some important ecological factors? At the heart of all of this is the question whether evolution is predictable and, more explicitly, whether we can predict a certain evolutionary outcome given certain information. This is important for at least two reasons. If we can predict a process, it’s probably fair to say that we have a decent understanding of it. Moreover, being able to predict evolution has vast applications ranging from our ability to fight diseases, combat the spread of invasive species, and counteract the detrimental effects of anthropogenic climate change. I have studied cases of parallel phenotypic evolution in Midas cichlids (Kautt et al. 2012, Elmer et al. 2014, Kautt et al. 2018) and African cichlids (Machado-Schiaffino et al. 2015).

Sympatric speciation – how can species arise without geographic barriers?

Sympatric speciation describes the process whereby a single population splits into two reproductively isolated species in the absence of geographic barriers. A bit more technically, sympatric speciation can be seen as the most extreme case of (primary) speciation-with-gene-flow. Because it is such an extreme case, true sympatric speciation is thought to be rare and occur only under very restricted conditions. In fact, whether sympatric speciation is possible at all has been the subject of one of the longest debates in evolutionary biology and at the heart of a rich body of theoretical and empirical research. Even today, only a few empirical case studies are generally accepted as credible examples of sympatric speciation. Among them are two small crater lake radiations of Midas cichlid fishes in Nicaragua. Midas cichlids represent a rare natural experiment of evolution, having independently colonized several crater lakes from the same great lake source populations and speciated in the absence of geographic barriers in some of them – but, interestingly, not in others. A main focus of my research has been to probe the overall evidence for sympatric speciation (Kautt et al. 2016), to investigate the ecological and demographic factors that may facilitate it (Kautt et al. 2018), and to study whether the genetic architecture of traits under divergent selection may affect whether sympatric speciation unfolds in this system (Kautt et al. 2020).

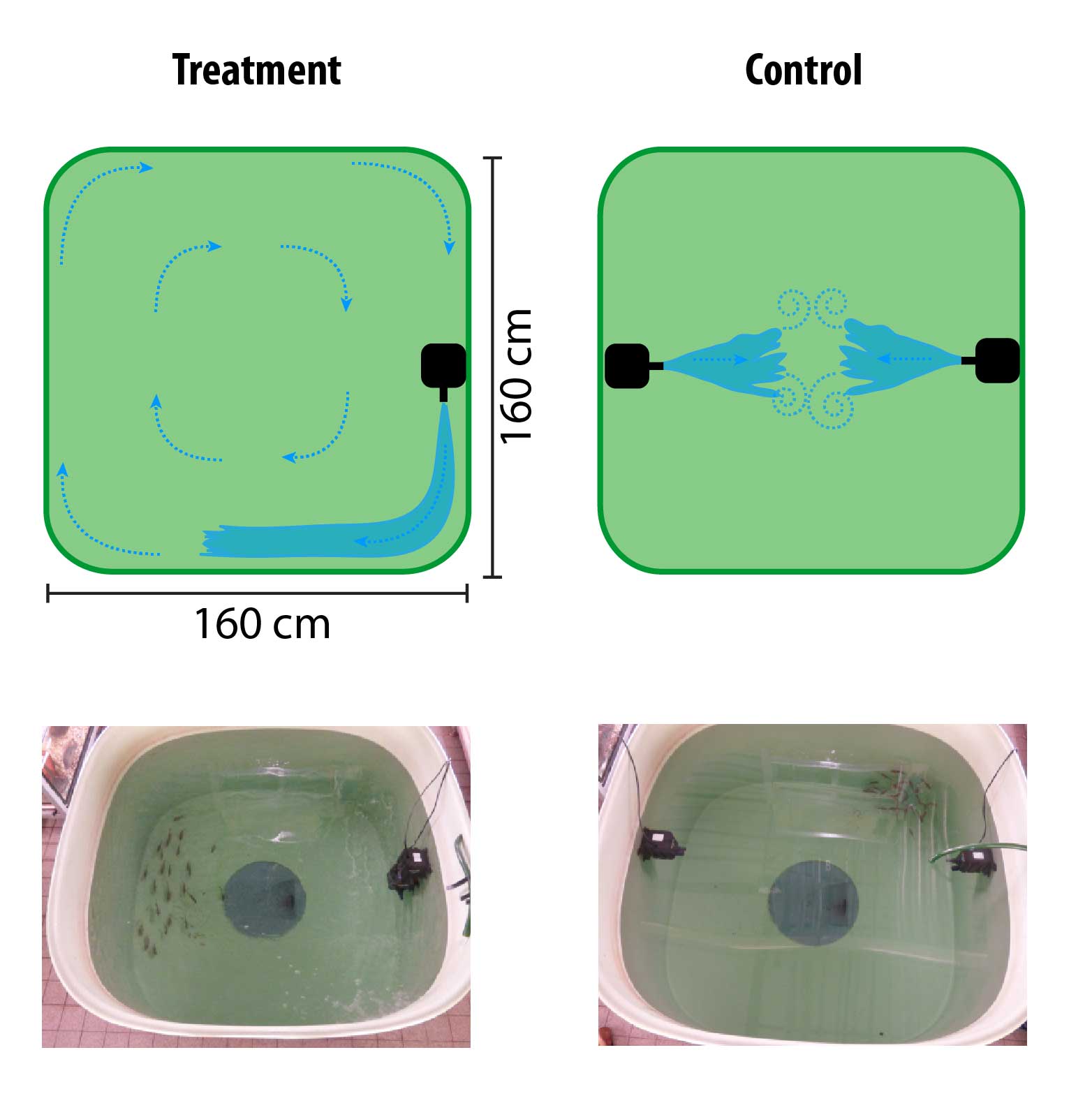

Integrative approach – molecular ecology, lab- and field experiments

I am primarily interested in the interplay of genotypes, phenotypes, and fitness (and how and when these dynamics lead to speciation). As mentioned above, to really understand these dynamics, complementary experiments in the lab and (if possible) in the field are invaluable and often necessary. Thus, apart from population genomic data analyses, my research includes geometric morphometrics (Kautt et al. 2018), stable isotope analyses (Kautt et al. 2016), mate choice experiments (Machado-Schiaffino et al. 2017, Kautt et al. 2020) and phenotypic plasticity experiments (Kautt et al. 2016) in the lab, as well as predation and performance experiments in the field (Torres-Dowdall et al. 2014).